Adaptation artist Lassa virus

Does it survive in multi-teat mice - and if so, for how many generations?

Lassa viruses can be transmitted through contact with multi-teat mice (Mastomys natalensis) and can cause severe to fatal fevers in humans. Rodents, on the other hand, hardly develop any symptoms. Researchers from the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (BNITM) and the University Medical Centre Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE) have been able to understand in detail for the first time how the viruses persist in their host animals over long periods of time. Their study was recently published in the journal Nature Communications.

The Lassa virus (LASV) belongs to the arena virus family and is endemic, i.e. firmly established, in several West African countries, particularly in Nigeria and Guinea. Humans can become infected through contact with the faeces of infected multi-teat mice (Mastomys natalensis). These often live in rural areas close to human settlements. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), between 100,000 and 300,000 people are infected every year, up to 10,000 of whom die after a severe course of haemorrhagic fever including internal bleeding and organ failure. There are neither authorised vaccines nor specific drugs. The Lassa virus (LASV) is therefore considered one of the world's most important pathogens with epidemic potential and must be analysed in the laboratory under the highest level 4 safety conditions. However, in its natural reservoir, the multi-teat mice (Mastomys natalensis), the virus only causes a ‘silent infection’: the infected animals show no signs of illness, but can transmit the virus in fields, villages and houses via their urine or faeces.

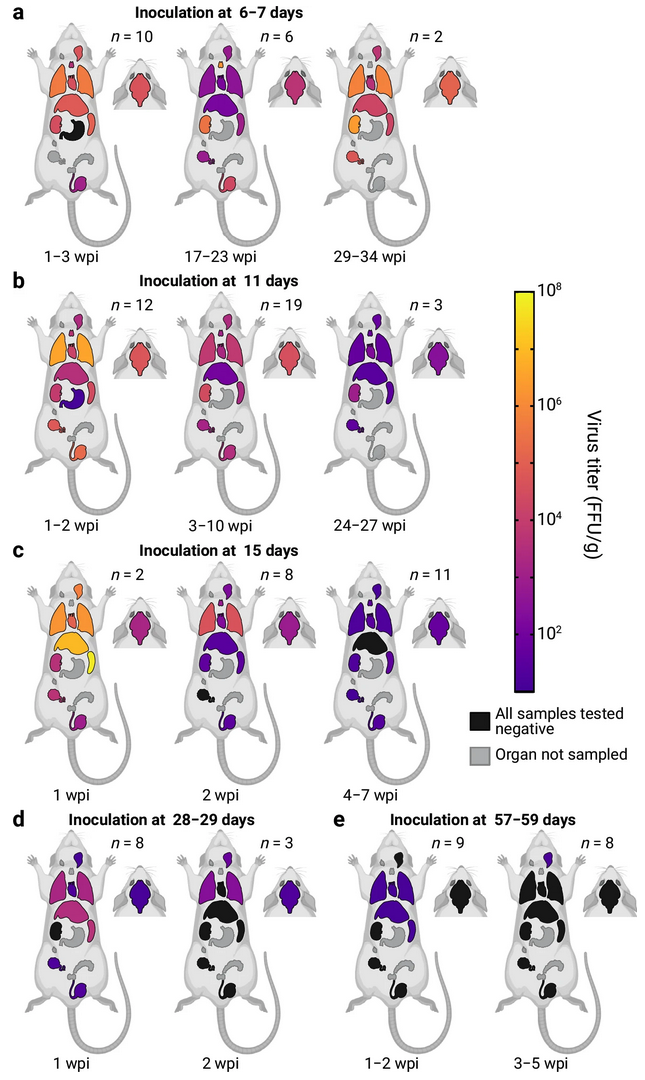

The research team led by Dr. Lisa Oestereich wanted to understand how the virus persists in the body of mice, apparently unnoticed by their immune system. They also wanted to clarify the role of sex and age in infection and transmission. To do this, they infected multi-teat mice with the Lassa virus strain Ba366 in a series of laboratory experiments. The researchers then observed the animals‘ health and behaviour, analysed the viral load in various organs and body fluids, and studied the immune response. In addition, they investigated whether the virus is transmitted from infected mothers to their offspring and how the animals’ susceptibility to infection changes with age.

Transmission between animals and generations

The infection experiments showed that susceptibility to long-lasting infections depends crucially on the age of the animals at the time of infection: particularly young animals under two weeks of age often developed a lifelong Lassa infection and remained permanent carriers of the virus, without their immune system being able to successfully fight off the pathogen, but also without the animals becoming ill. Older animals, on the other hand, were able to fight off the virus within a few weeks.

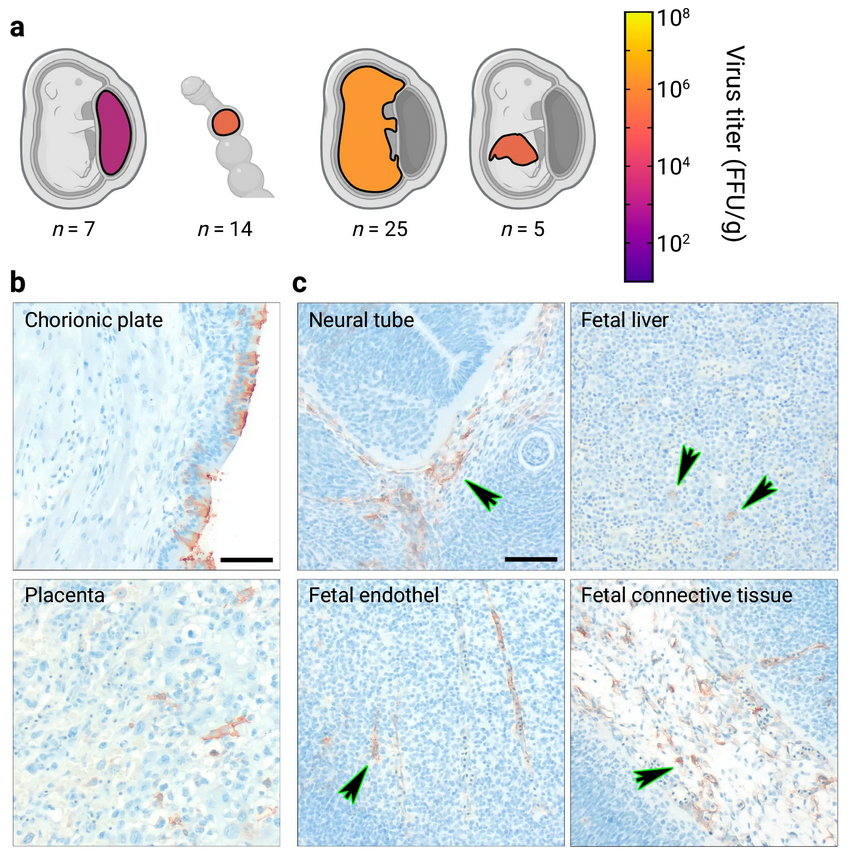

It was also remarkable that infected females transmitted the virus to almost all of their offspring via the placenta or after birth, enabling the virus to become established in the mouse population over generations. LASV is thus transmitted both horizontally between conspecifics and vertically from infected mothers to their offspring. In short, infected females play a key role in the persistence of the virus in the mouse population.

No symptoms of disease despite high viral load

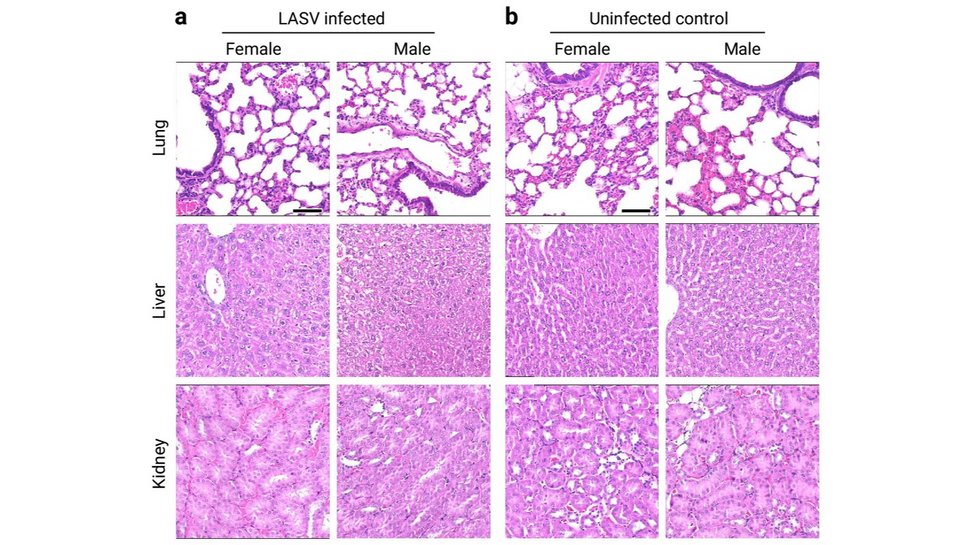

One surprising result of the study is that infected Mastomys natalensis remain healthy even when they carry the virus for life. The researchers observed no tissue damage or other signs of disease. The virus also had no negative impact on the growth and reproduction of the infected animals. However, it was detectable in high concentrations in various organs – especially in the kidneys, lungs and genital organs – particularly in the epithelial cells of these organs.

According to the research team, this behaviour of the virus could give LASV an evolutionary advantage: it remains stable in a host that does not develop any symptoms and can thus pass to many other individuals via excreta or during reproduction without affecting the host's health.

‘Our research illustrates for the first time the mechanism by which the virus stabilises in nature,’ says Lisa Oestereich, last author of the study and junior research group leader at BNITM. ’It shows that it is the early infection that provides the virus with a niche in young mice in which it can persist for long periods of time.’

Implications for health protection in West Africa

First author of the study Dr Chris Hoffmann adds: ‘Our research results could be of great importance for understanding and preventing Lassa fever. They explain why the Lassa virus remains dangerously close to humans and comes into contact with them again and again.’

Detailed research into how the Lassa virus survives and is passed on in its natural host may lead to the development of new measures to reduce the risk of infection in humans in the future.

Original publication

Hoffmann, C., Krasemann, S., Wurr, S. et al.: Lassa virus persistence with high viral titers following experimental infection in its natural reservoir host, Mastomys natalensis. Nat Commun15, 9319 (2024).

doi.org/10.1038/s41467-024-53616-4

Contact person

Dr Lisa Oestereich

Research Group Leader

Phone : +49 40 285380-940

Email : oestereich@bnitm.de

Julia Rauner

Public Relations

Phone : +49 40 285380-264

Email : presse@bnitm.de

Dr Anna Hein

Public Relations

Phone : +49 40 285380-269

Email : presse@bnitm.de

Further information