FAQ on Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs)

Disclaimer

The contents of this website are for general information purposes only and do not constitute medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. They are not a substitute for individual consultation with a qualified medical professional.

No guarantee is given for the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of the information provided. Use of the content is at your own risk. If you have any health questions or complaints, please always consult a doctor or other qualified professional.

Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) are among the poverty-associated infectious diseases. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has recognised a diverse group of 21 infectious diseases and snakebite envenoming as NTDs, including diseases caused by worms, protozoa, bacteria or viruses. The WHO list includes:

Buruli ulcer; Chagas disease; dengue and chikungunya; dracunculiasis; echinococcosis; foodborne trematodiases; human African trypanosomiasis; leishmaniasis; leprosy; lymphatic filariasis; mycetoma, chromoblastomycosis and other deep mycoses; noma; onchocerciasis; rabies; scabies and other ectoparasitoses; schistosomiasis; soil-transmitted helminthiases; snakebite envenoming; taeniasis/cysticercosis; trachoma; yaws.

These diseases occur mainly in poorer countries with poor hygienic conditions and tropical climates. There, pathogens and vectors such as certain mosquito species can proliferate. However, due to global warming, global travel and migration, countries in temperate zones are also increasingly affected. Occasionally, travellers also fall ill.

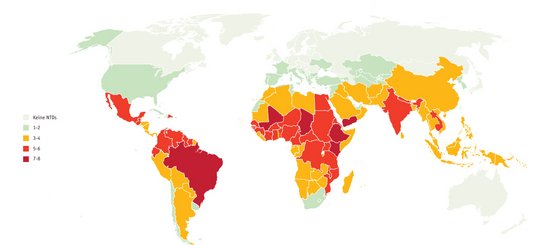

Where do neglected tropical diseases occur?

Distribution of NTDs in the world

In 2020, Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs) affected 1.7 billion people in 149 countries worldwide, with another two billion at risk. NTDs affect the poorest parts of the population in already poor countries. They usually do not lead directly to death, but often to severe and long-lasting diseases, some of which are chronic. Many patients suffer disabilities, become blind or disfigured, have chronic or recurring pain, become unable to work, experience discrimination and sometimes also become mentally ill.

Neglected tropical diseases are therefore a great burden for those affected and their families and subsequently also for the economic situation of the countries: the high burden of disease in the population prevents them from sustainable development.

In 2017, the WHO proclaimed the goal of greatly reducing neglected tropical diseases by 2030. Many can already be prevented or treated today, while others lack effective diagnostics, medicines and vaccinations. Often, however, the necessary financial resources for drugs, their distribution, awareness campaigns and research are lacking. World NTD Day on 30 January aims to raise awareness of this.

What is the BNITM doing about Neglected Tropical Diseases?

In June 2022, BNITM signed the "Kigali Declaration on Neglected Tropical Diseases (NTDs)". The declaration supports the WHO's roadmap to reduce the number of infections by 90%, eliminate at least one NTD in 100 countries by 2030 and completely eradicate two NTDs.

BNITM conducts research on various NTDs, including leishmaniasis, snakebites, schistosomiasis and other worm infections. At the same time, researchers have been able to show that other infections, for example with the eye worm Loa loa, also represent a significant burden of disease for affected individuals, contrary to earlier assumptions.

Schistosomiasis

Among NTDs, schistosomiasis ranks first in terms of years of life lost to premature death or disability. The infection is caused by fork-tailed larvae, so-called cercariae, which penetrate the skin of humans when they come into contact with contaminated water. From there, they migrate via the lymphatic and blood vessels into the vascular plexus of the intestinal tract or the urinary bladder. Here, within a few weeks, adult worms about 2 cm in size develop and regularly release eggs. These eggs can then lead to chronic inflammation in the intestinal and bladder tissue as well as in other organs such as the liver and kidneys, with sometimes serious late consequences such as liver fibrosis or bladder cancer.

The BNITM laboratory group "Combating Poverty-Related and Neglected Tropical Diseases" seeks solutions for the prevention and management of diseases of poverty. Its focus is schistosomiasis and its consequences. The group conducts most of its studies in Madagascar. There, schistosomiasis is still endemic. Among the affected countries, the island nation east of Africa is one of the countries with the highest prevalence of schistosomiasis worldwide. The researchers are conducting further studies with partner organisations in sub-Saharan Africa.

Female genital schistosomiasis (FGS) is a common chronic development of schistosomiasis that can lead to infertility, among other things. The freeBILly und FIRMUP projects therefore focus on female patients in particular.

"Health care is a human right and for this reason diseases shouldn’t be neglected. My motivation is to give a voice to marginalised populations. Moreover, I strongly believe that globalisation and climate change will bring NTDs from the tropics also to other parts of the world in the coming decades. In the context of global health, diseases are relevant regardless of their geographical location and should be considered because of the overall burden they (can) cause."

Daniela Fusco, Ph.D., Lab group leader

Snakebite Envenoming

The link between poverty and neglected tropical diseases is particularly striking in the case of snakebite envenoming. Unlike many other serious diseases, there are highly effective treatment options: namely, antivenoms. According to the Word Health Organisation WHO, most deaths would be completely preventable if safe and effective snake antivenoms were more available and accessible. With them, most symptoms resulting from snakebites can be prevented or reversed. They are included in the WHO list of essential medicines and should be part of any primary health care for snakebite.

The WHO estimates that snakes bite about 5.4 million people every year, and poison 2.7 million of them. Up to 140,000 of the victims die as a result of snakebites, about three times as many are injured.

Snakebites can cause bleeding and paralysis, obstruct breathing, tissue damage, kidney failure, permanent disability and limb amputation. This is often compounded by stigmatisation, social exclusion and subsequent mental illness.

People in rural regions of Africa, Asia and Latin America are most affected. Children often suffer more severe effects than adults due to their smaller body mass.

Three things count when it comes to treating snakebites: speed, trained medical staff and an effective antivenom. There is too little of all of these in many affected areas.

The working group Snakebite Envenoming together with local partners, is conducting studies on the epidemiology of snakebites and venomous snakes in different geographical regions. It researches the availability of suitable and effective antivenoms as well as clinical aspects of snakebites.

In addition, the team trains medical staff in the treatment of snakebites and develops guidelines adapted to the respective national circumstances.

"I had my pivotal moment as a doctor in training in the intensive care unit of a provincial hospital in Laos: a patient had been bitten on the right foot by a Malayan pit viper and had developed life-threatening anaemia. My Lao colleagues and I stood at the patient's bedside, perplexed. No one had experience in treating venomous snakebites. An antivenom was not available in our hospital pharmacy or elsewhere in Laos. Fortunately, the patient survived after receiving more than ten blood transfusions. With antivenin we could have quickly fixed the massive blood clotting disorder and prevented the anaemia with the necessary transfusions."

Dr Jörg Blessmann, Working Group Leader

Leishmaniose

Leishmaniasis infections occur worldwide, both in humans and in animals, mostly rodents. The Leishmania parasites are transmitted to mammals by bloodsucking sandflies. They can cause self-healing skin lesions, known as Oriental bumps, as well as large dry and non-healing skin ulcers. Visceral (internal) leishmaniasis (kala-azar) is almost always fatal if left untreated.

WHO estimates that more than 12 million people are currently infected and more than 1 million people become newly infected each year. In North Africa and the Middle East, and especially in Syria, cutaneous leishmaniasis is particularly widespread, while European visceral leishmaniasis predominantly affects dogs and usually only causes disease in immunocompromised people. Thus, leishmaniasis is considered an important complication of HIV infections, as both misdirect the human immune system. This favours both HIV infection and leishmaniasis and makes treatment of leishmaniasis much more difficult.

Transmission of leishmaniasis in Germany is very rare, as the transmitting sandflies do not occur in Germany or not in significant numbers. So far, domestic sandfly species have not been associated with transmission. However, due to climate change, the transmitting sandfly species are spreading northwards and could also become native to southern Germany if the climate warms further.

The research group led by PD Dr Joachim Clos is investigating the genetics of Leishmania parasites. It investigates the role and function of certain key proteins during the life cycle, the control of differentiation between the life cycle stages and the influence of the Leishmania infection on the biology of the host cells. In doing so, it cooperates with Prof. Dr Hanna Lotter's research group and also tries to find out on a molecular level why Leishmania infections progress differently in men and women.

Worm diseases

The World Health Organisation (WHO) estimates that one in four people is still infected with parasitic worms, so-called helminths. Again, the link between poverty and disease, poor sanitation and transmission routes is particularly striking: the poorest and most disadvantaged communities with poor access to clean water and sanitation are affected, especially in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and South America. Helminths are transmitted by eggs in human faeces, which in turn contaminate the soil in areas with poor sanitation.

Helminth infections disrupt child development and growth; infected women and girls of childbearing age suffer from iron deficiency due to blood loss. This increases the risk of maternal and infant mortality and low birth weight. There are safe and effective drugs to treat helminth infections.

Infection and immune response: a complex interplay

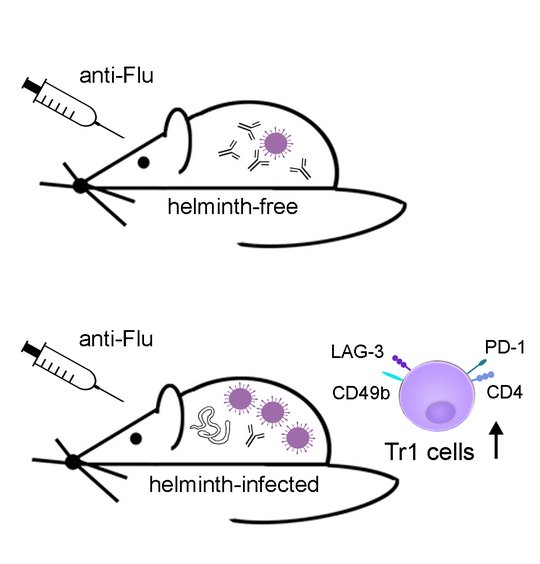

Parasitic helminths have developed a rather successful survival strategy in the course of evolution: In order not to be eliminated, they actively dampen the immune response of their hosts (immunomodulation). However, in doing so, they also interfere with their immune response to other infectious agents. Prof. Dr Minka Breloer's research group has shown this in a mouse model: flu vaccinations, for example, worked worse in worm-infected mice than in healthy mice - not only in acute worm infections, but even after they had recovered. This should be taken into account when developing vaccines.

The researchers are using the parasitic nematode Strongyloides ratti to study its immune modulation in the mouse system. They are interested in the mechanisms of protective antihelminth immunity, the mechanisms of helminth-induced immunomodulation and the effects of concurrent helminth infection on the outcome of vaccination against different pathogens.

"Neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) are drivers of inequality. This leads to poverty, with all its consequences. The only way to fight NTDs is to develop a comprehensive understanding of what factors lead to them. I think this is where we NTD scientists play a crucial role. Ultimately, science in general plays a key role in combating NTDs."

Dr Ricardo Strauß, Department of Infectious Disease Epidemiology

"Infection with pork tapeworms can lead to neurological disorders such as epileptic seizures. When I lived in sub-Saharan Africa, I realised what it means to live with a higher risk of disease but have poor health care: Many people with so-called neurocysticercosis (NCC) were travelling for days to pick up their medication at the health centre. Some came with severe wounds like burns because they had fallen into the fire during an attack." BNITM scientist

Contact

- Prof. Dr Jürgen May

- Head of Dpt. Infectious Diseases Epidemiology

- phone: +49 40 285380-402

- email: may@bnitm.de

- Dr Anna Hein

- Public Relations

- phone: +49 40 285380-269

- email: presse@bnitm.de

- Julia Rauner

- Public Relations

- phone: +49 40 285380-264

- email: presse@bnitm.de

- The Laboratory diagnostics|Consultation for physicians

- Advice on the diagnostic procedure

- phone: +49 40 285380-211

- fax: +49 40 285380-252

- email: labordiagnostik@bnitm.de