Lassa fever much more common than previously thought

New insights into the spread, immunity, and prevention of Lassa fever

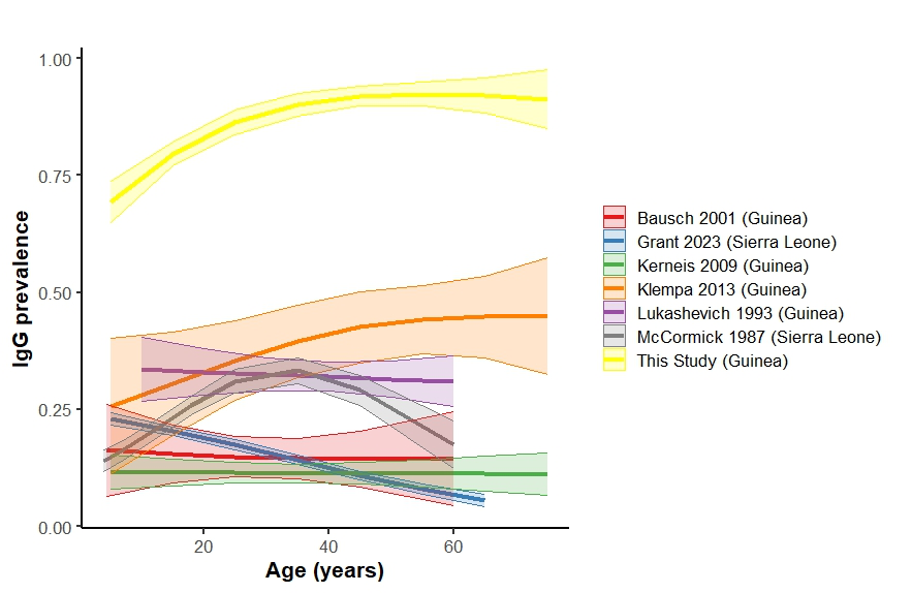

A large proportion of the population in rural Guinea is exposed to the Lassa virus at a very young age. In six villages in the Faranah region, over 80 percent of study participants were found to possess IgG antibodies against the virus – a significantly higher rate than reported in previous studies from West Africa. These are the findings of a study led by researchers at the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (BNITM). Published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases, the study results challenge key assumptions about the frequency, severity, and control of Lassa fever.

Lassa fever is a zoonotic disease (transmitted from animals to humans) caused by the Lassa virus. It is widespread in West Africa. The main reservoir of Lassa virus are rodents, particularly the multimammate mouse Mastomys natalensis, which commonly live in close proximity to humans. Due to inadequate diagnostics and underreporting, the true scale of this haemorrhagic fever disease remains difficult to determine.

Lassafever as part of everyday life?

The research team analysed more than 1,300 blood samples from residents of six remote villages where a high prevalence of Lassa virus-positive rodents had been documented. More than half of the children under five years of age already had IgG antibodies against the Lassa virus, indicating they had previously been infected.

“We found that many inhabitants had already contracted the virus as children, without noticing. In this region, infection seems to be part of everyday life,” explains Dr Elisabeth Fichet-Calvet of BNITM, who coordinated the study.

Regardless of age, more than 80 per cent of the participants had been in contact with the Lassa virus – the highest seroprevalence ever recorded in a healthy population in West Africa. Previous studies reported rates between 5 and 50 per cent. The researchers also modelled, based on the antibody waning rate, that Lassa virus-specific IgG antibodies remain detectable in the blood for an average of 58 years, indicating the possibility of lifelong immunity.

IgM antibody levels – which point to recent Lassa virus infections – remained consistent across all age groups at around 1.8 per ent. This suggests continuous transmission of the Lassa virus within the population. However, very few acute Lassa fever cases have been reported in the region, indicating that many infections are either mild or asymptomatic, or are frequently mistaken for other illnesses such as malaria.

“Our results show that Lassa fever occurs much more frequently in some regions than previously assumed. However, many infections seem to go unnoticed,” says Fichet-Calvet, head of the research group Zoonoses Control.

Using mathematical modelling, the researchers calculated how the rate of virus transmission from animal reservoirs to humans could be effectively reduced. Their conclusion: to cut the number of human infections by half, the rate of spillover from animals would need to be reduced by a factor of ten – a goal that is virtually unfeasible in practice.

New perspectives for epidemiology and prevention

The study not only provides a realistic picture of the Lassa virus spread in rural areas, but also shows that many epidemiological models have significantly underestimated the virus. Earlier estimates put the number of infections in West Africa at 200,000 to 300,000 per year. In alignment with recent model-based studies, this study’s estimate is over 900,000 – possibly exceeding one million annually.

Children are exposed to the Lassa virus early in life. As a result, they often develop a protective immune response, which suggests that reinfections in adulthood might be less likely to lead to severe illness.

“Therefore, vaccination of children against the Lassa virus could be a more effective strategy than relying solely on rodent control or behavioural change,” says Fichet-Calvet. “The latter are difficult to implement for ecological, cultural and logistical reasons – especially in rural areas with close human-animal contact.”

Researchers from BNITM conducted the study in close collaboration with partner institutions in Guinea, Germany, Belgium and the USA. The study was funded by the German Research Foundation (DFG) and the European Union's Horizon Europe research programme.

Original publication:

Contact person

PhD Elisabeth Fichet-Calvet

Research Group Leader

Phone : +49 40 285380-942

Email : fichet-calvet@bnitm.de

Dr Anna Hein

Public Relations

Phone : +49 40 285380-269

Email : presse@bnitm.de

Further information