Proteins in the blood plasma of malaria patients set inflammatory processes in motion

In a study on the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum, the research group led by Prof. Iris Bruchhaus from the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (BNITM) has shown for the first time that proteins in the blood plasma of malaria patients also influence the production of inflammatory messengers. Previously, research groups assumed that these messengers are only released when infected red blood cells attach themselves to the walls of blood vessels. The research was published in the journal Cells in July 2021.

Malaria is the most important tropical disease that kills around 400,000 people worldwide. The majority of deaths occur after infection with Plasmodium falciparum in Africa. This parasite causes the particularly severe infections by infecting red blood cells and the infected red blood cells eventually bind to the walls of blood vessels. The binding leads to a blockage of small blood vessels, oxygen deficiency and activation of the immune system. This can lead to organ failure and also damage to the brain (cerebral malaria).

The activation of the immune system is characterised by an increased concentration of different messenger substances (cytokines) in the blood of malaria patients. In particular, the cells of the blood vessels, the so-called endothelial cells, are a potential source of these cytokines. So far, more than 30 different cytokines have been detected in elevated concentrations in the plasma of malaria patients. It was not known until now whether the release of these messenger substances can only be stimulated by the direct contact of the red blood cells infected with P. falciparum with the endothelial cells or also contact-independently.

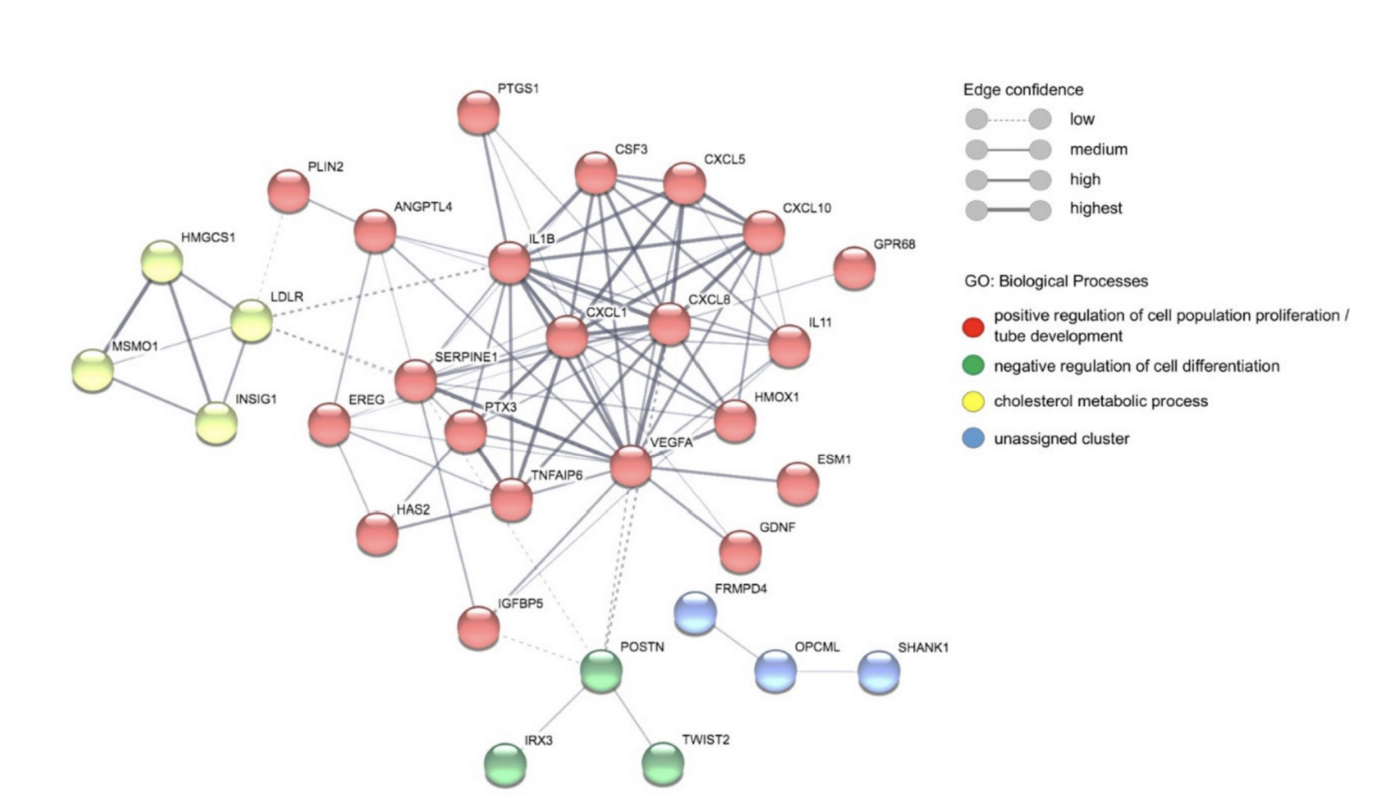

The Bruchhaus working group demonstrated that endothelial cells mixed with plasma from malaria patients secrete various cytokines and growth factors. In a parallel study, the team investigated which RNA molecules are produced by endothelial cells when they are exposed to patient plasma. This so-called transcriptome analysis confirmed the results of the increased production of various cytokines described above. The research group was thus able to show that not only the direct binding of infected red blood cells, but also molecules in the plasma of malaria patients influence the endothelial cells of the blood vessels. This not only affects the immunological response, but also other processes such as cell proliferation and the formation of blood vessels.

Background

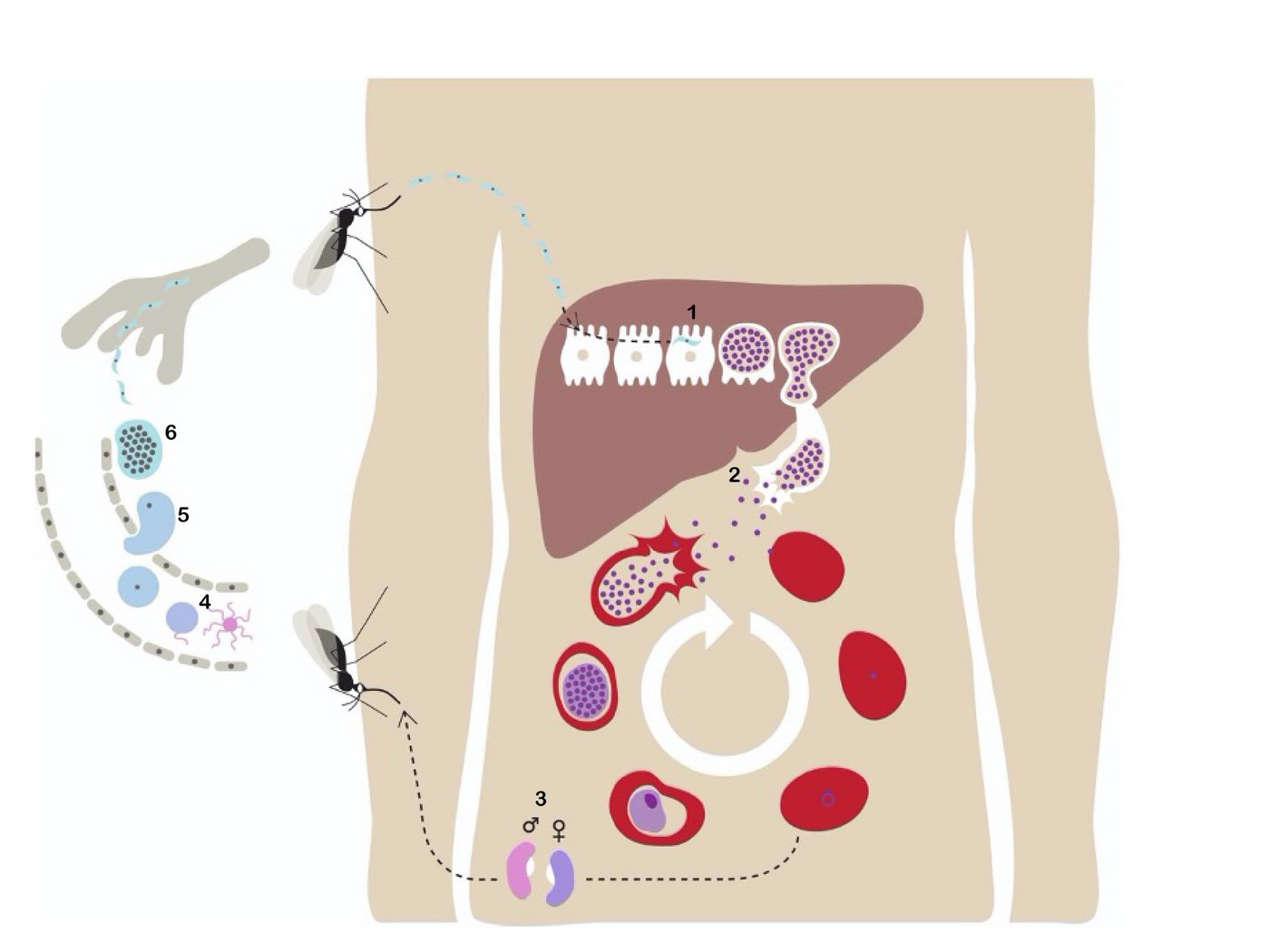

The malaria pathogen P. falciparum is a parasite and is transmitted to humans through the bite of an infected female Anopheles mosquito. The parasites in the form of sporozoites (1) migrate to the human liver where they reproduce asexually and do not cause any symptoms. The parasites in the form of merozoites (2) are subsequently released into the bloodstream, penetrate the red blood cells and multiply again. After the red blood cells burst open, they invade more red blood cells. This cycle repeats and causes a fever response whenever the parasites break out and invade the blood cells again. Some of the merozoites develop into sexual forms of the parasite called gametocytes (3), which circulate in the bloodstream. When a mosquito bites an infected person, it ingests the gametocytes, which develop into mature gametes (4). The fertilised (5) female gametes develop into oocysts (6) in which thousands of sporozoites mature. The oocysts eventually burst, releasing sporozoites that migrate to the mosquito's salivary glands. If a human is then bitten, the cycle is closed.

Despite advances in malaria control programmes, malaria remains one of the most devastating infectious diseases worldwide. Of the five species that cause malaria in humans, Plasmodium falciparum is the most clinically significant and responsible for the most deaths. In 2019, 229 million people suffered from malaria; around 409,000 people died from it. The Corona pandemic has further worsened this situation, as mosquito control programmes could no longer be implemented in many places.

About the Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine

The Bernhard Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine (BNITM) is an institute of the Leibniz Association and Germany's largest institution for research, care and teaching in the field of tropical and emerging infectious diseases. Current research focuses on malaria, haemorrhagic fever viruses, immunology, epidemiology and clinic of tropical infections as well as the mechanisms of virus transmission by mosquitoes. For handling highly pathogenic viruses and infected insects, the institute has laboratories of the highest biological safety level (BSL4) and a safety insectarium (BSL3). BNITM includes the national reference centre for the detection of all tropical infectious agents and the WHO collaborating centre for arboviruses and haemorrhagic fever viruses. Together with the Ghanaian Ministry of Health and the University of Kumasi, it operates a modern research and training centre in the West African rainforest, which is also available to external working groups.

Contact person

Prof. Dr Iris Bruchhaus

Research Group Leader

Phone : +49 40 285380-472

Email : bruchhaus@bnitm.de

Dr Eleonora Schoenherr

Public Relations

Phone : +49 40 285380-269

Email : presse@bnitm.de